CourseCompendium

Heidegger

RELATED TERMS: Arendt; Sloterdijk; Lefebvre; Present-at-hand (Vorhanden) and Ready-to-hand (Zuhanden); Everyday; Philosophy

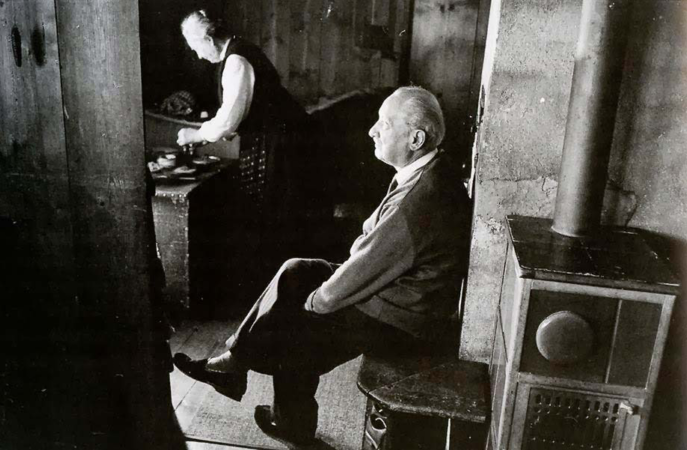

The work of Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) is of great relevance to the design and analysis of narrative environments because it deals with spatio-temporal ways of being in the world and contains concepts such as Dasein (ex-sistence), present-at-hand and ready-to-hand, which might be of value in design contexts, so long as they are not uncritically appropriated.

Heidegger’s work is also of relevance because of its influence on others, such as Henri Lefebvre, Michel Foucault and Peter Sloterdijk. For example, even as Lefebvre distanced himself from Heidegger, seeing Heidegger’s Holderlin-inspired poetic critique of habitat and industrial space as a critique from the right, nostalgic and old-fashioned, Lefebvre’s emphasis on space is indebted to Heidegger’s inauguration of space as a problematique, while Foucault took Heideggerean ideas forward in his analysis of the relation between history and space (Elden, 2004).

However, use of his work can only proceed with great caution. Firstly, he held a mostly negative view of modernity, the processes of modernisation and the modern world, and therefore his work will be of limited value in discussing modern and contemporary issues. He idealised rural life in late-19th-century Germany and experienced discomfort at the flourishing of German science and technology after 1860.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, a major difficulty in using Heidegger’s work lies in his involvement in politics, and the relation of that involvement to his philosophy. It is a topic that has generated acrimonious disagreement [1].

One central question is whether Heidegger’s Nazism was a passing aberration or a lasting commitment. There can be little doubt that his politics are connected to some enduring elements of his philosophy. Heidegger believed that a moment of communal authenticity, as discussed in section 74 of Being and Time, had arrived. Utilising his understanding of historicity, he held that a movement based on a particular people’s heritage was truer and deeper than any politics based on universal, abstract principles, such as liberal democracy or communism, as he understood them (Fried and Polt, 2014: xiv).

However, this is not to conclude that his philosophical ideas can only lead to fascist politics or that his ideas are exhausted by such politics. Heidegger distanced himself increasingly from Nazism, or rather from the actual practice and dominant mentality of the movement, as distinct from its “inner truth and greatness” (Heidegger, 2014: 222). By 1940, Heidegger had developed a metaphysical critique of standard Nazi ideology, without drawing closer to a liberal or leftist position.

In his thinking from the mid- to late-1930s, Heidegger shifts towards a new, historical understanding of Being: being is to be grasped as a fundamental happening, the appropriating event (das Ereignis). The event can found Dasein by opening a time-space or site of the moment where Dasein is appropriated. Genuine selfhood can then be achieved and people can learn to shelter truth in particular beings, such as works of art, but only if truth is understood as openness to the meaningfulness of things, not as a set of correct propositions about the world that we hide away and safeguard.

It was such an appropriating event that Heidegger had been hoping to find in the National Socialist revolution. Nevertheless, in Contributions to Philosophy, a text written in the mid-1930s but not published until after his death, Heidegger submits the typical Nazi worldview to strong criticism, insisting that a Volk is never an end in itself. From this point onwards, Heidegger begins to look less towards politics and more toward poetry, specifically that of Holderlin, in order to consider new ways for the Germans to seek themselves. Heidegger’s late writings move even further from the domains of wilful action and power, emphasising the need for patience.

In the speeches, lecture courses and seminars from his year as rector of the University of Freiburg in 1933-1934, Heidegger speaks as an enthusiast of National Socialism. By the time of writing Introduction to Metaphysics in 1935, his enthusiasm is waning and he has become engaged in an internal critique of National Socialism, in an effort to be more radically revolutionary than the Nazi revolution itself. Fried and Polt (2014: xviii) suggest that the question of whether Heidegger is a Nazi in Introduction to Metaphysics, because he surely is, is less interesting than the question of what it means to be a Nazi, a question which Heidegger raises in that text, as well as broader questions about what it means to be German, to be Western and to be human.

While the lines of questioning he begins are irreducible to a particular political party’s programme or ideology, the text nonetheless resonates with the most terrifying aspect of the Nazi movement, its readiness to commit violence and murder against its perceived enemies. Heidegger explores the idea that human beings, or at least great ones, are uncanny and violent. They must fight against other beings and against Being itself until they are inevitably and tragically crushed by the overwhelming power of Being. Throughout the mid-1930s, Heidegger seems to celebrate creative conflict (creative destruction). He seems also to believe that National Socialism may find an appropriate way to spur such creativity and revive an ancient understanding of techne as a forceful and disclosive struggle (Fried and Polt, 2014: xx).

However, with his turn away from power and will, and his development of a critique of modern technology, Heidegger develops a less violent understanding of human greatness, as he continues to explore the dimensions of what he considers to be primordial phenomena: beings, Being and Dasein or ex-sistence. Thomas Sheehan (2014) is of the view that Heidegger did not get beyond the essence of human being as ex-sistence, a term that Sheehan prefers to Dasein. Human ex-sistence, Sheehan explains,

“consists in our being made to “stand out ahead” of ourselves as a groundless “openness” or clearing.” Within this openness we can synthesize this object here with that meaning there and thus understand the thing’s current “being,” i.e., what it currently is for us or better, how it is meaningfully present to us. Thus our essence as ex-sistence is what allows for all forms of “being”… “

This, Sheehan concludes, answers Heidegger’s basic question: “Whence the ‘being’ of things?”

Notes

[1] To find out more about Heidegger, philosophy and politics, the following books are of great value:

Farias, V. (1989). Heidegger and nazism, edited by J. Margolis and T. Rockmore. Philadelphia, Temple University Press.

Faye, E. (2009). Heidegger, the introduction of Nazism into philosophy in light of the unpublished seminars of 1933-1935. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Fried, G. (2000). Heidegger’s polemos: from being to politics. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Ott, H. (1993). Martin Heidegger: a political life. Hammersmith, London: HarperCollinsPublishers.

Rockmore, T., & Margolis, J. (1992). The Heidegger case: on philosophy and politics. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Safranski, R. (1998). Martin Heidegger: between good and evil. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wolin, R., ed. (1993). The Heidegger controversy: a critical reader. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

For a recent evaluation of Heidegger scholarship, see:

Sheehan, T. (2014). Making sense of Heidegger: a paradigm shift. London: Rowman and Littlefield International.

References

Elden, S. (2004). Between Marx and Heidegger: politics, philosophy and Lefebvre’s The Production of Space. Antipode, 36 (1), 86–105. Available from http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2004.00383.x

Fried, G. and Polt, R. (2014). Translators’ introduction to the second edition. In: Introduction to metaphysics, 2nd ed., by Martin Heidegger. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Heidegger, M. (2014). Introduction to metaphysics. Revised and expanded translation by Gregory Fried and Richard Polt, 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sheehan, T., Polt, R. and Fried, G. (2014). No one can jump over his own shadow. 3:AM Magazine, (8 December). Available from http://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/no-one-can-jump-over-his-own-shadow/ [Accessed 1 September 2016].